Father/daughter relationships can be fractious at best of times. Either the former is too protective of the latter, becoming inadvertently overbearing and prescriptive or, conversely, too immersed in work or personal projects and thus aloof and distant. It’s rare the father that can tread this tightrope successfully. It’s this relationship that Mary Talbot examines in her new graphic novel, Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes. Juxtaposing her own relationship with her father, James S. Atherton, a noted Joycean scholar, with that of James Joyce and his daughter Lucia, Talbot has created a bittersweet drama that will resonate with anyone who has a parent.

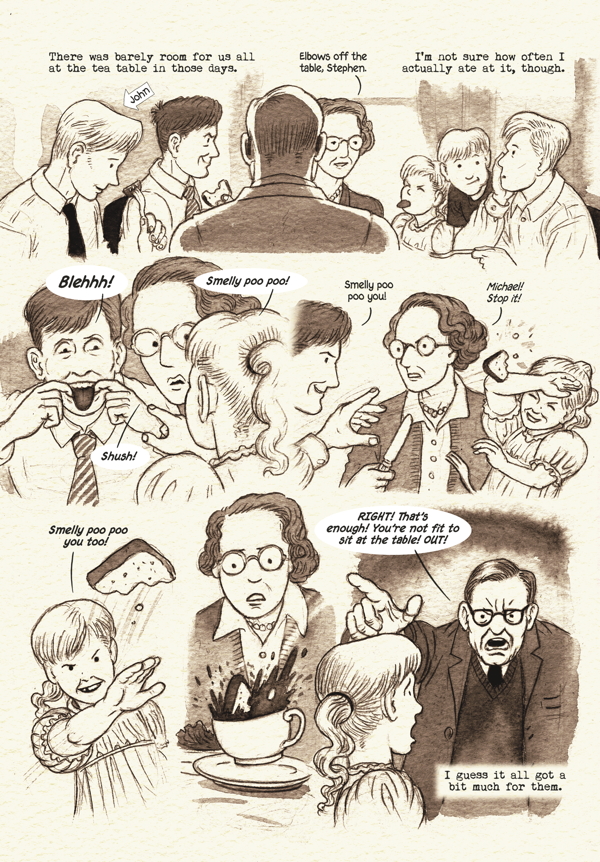

For a debut graphic novel Mary’s writing is incredibly confident and assured. This may be partly due to her being an established, published scholar in her own right, and partly due to the fact that the book is drawn by her husband, Bryan, one of the UK’s most accomplished masters of the art. Bryan’s artwork mellifluously transports us up and down the timeline so effortlessly that we simply go with the flow. He very cleverly uses highly simplified, full-colour Julian Opie-like characters for the present day and Mary’s life story; a washed out sepia tone for Mary’s post-war childhood; and finally, a more rendered reality in a blue-wash to recount the tale of Lucia.

The majority of this collaborative endeavour is incredibly smooth, but there are a couple of points where Mrs. Talbot has to highlight her husband’s inaccuracies (such as how her classroom was laid out) in margin notes. While this is an endearing insight into the creative process, it feels like too much fourth wall breaking to sit comfortably, instantly reminding the reader that they are reading a graphic novel, rather than being engrossed in the fascinating tale.

Perhaps it is unsurprising that Mary’s academic career has focused on gender politics and power, once you have read this story. Being the only daughter with four elder brothers; a domineering father; the appalling repression and treatment meted out to women in the pre-Feminism era; and that she had two sons; all indicate a natural, and understandable, desire to readdress the balance somewhat. Yet despite the obviously painful, and joyful, recollections, and analysis of her relationship with her father, Mary never descends into mawkishness or hand-wringing self-pity, and remains refreshingly clear of the mire of the “misery memoir” that the book could so easily have become. Mary’s writing remains constantly engaging, and brings every character to vibrant, empathic life, as she contrasts her coming-of-age with that of Lucia’s. Where Mary’s father seems distant yet authoritarian, Joyce appears weaker, agreeing with his wife Nora’s more bombastic and conservative views on womanhood, as both girls are belittled for failing to live up to their parents’ expectations. Thankfully, Mary’s tale ends happier than the tragic Lucia’s, but both resonate long after the final page has been turned. This is destined to become a set text for graphic novel scholars.

I’ll confess my ignorance when it comes to Joyce, but this book sparked an interest in his life and writing and I started actively searching out further information, and no greater compliment can be paid than that. Fortunately there’s a comprehensive bibliography in the back.

Most fathers remain enigmas to their children, and it’s this attempt to understand her father’s motivations and moods—to get behind both his public and home personas, and in turn closure—that makes Mary’s writing so intriguing. Like the title’s pun suggests, Mary Talbot is wrapping up her father’s business, his memory and legacy. Dotting his eyes and crossing his tease.

Leave a Reply